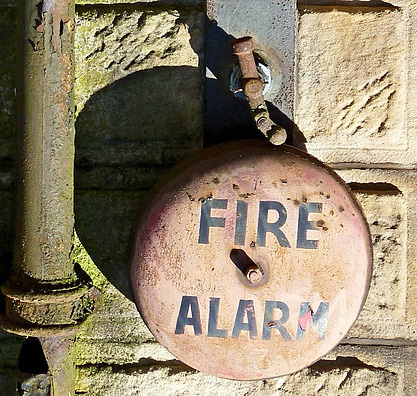

The Fire Alarm is Ringing. What Are You Waiting For?

How a fear of change can prevent you from acting when it matters most.

In the New York Times, Michiko Kakutani wrote that Stephen Grosz’s The Examined Life “distills the author’s twenty five years of work as a psychoanalyst and more than 50,000 hours of conversation into a series of slim, piercing chapters that read like a combination of Chekhov and Oliver Sacks.” What follows is an excerpt from the book, in stores now.

When the first plane hit the north tower of the World Trade Center, Marissa Panigrosso was on the ninety-eighth floor of the south tower, talking to two of her co-workers. She felt the explosion as much as heard it. A blast of hot air hit her face, as if an oven door had just been opened. A wave of anxiety swept through the office. Marissa Panigrosso didn’t pause to turn off her computer, or even to pick up her purse. She walked to the nearest emergency exit and left the building.

When the first plane hit the north tower of the World Trade Center, Marissa Panigrosso was on the ninety-eighth floor of the south tower, talking to two of her co-workers. She felt the explosion as much as heard it. A blast of hot air hit her face, as if an oven door had just been opened. A wave of anxiety swept through the office. Marissa Panigrosso didn’t pause to turn off her computer, or even to pick up her purse. She walked to the nearest emergency exit and left the building.

The two women she was talking to – including the colleague who shared her cubicle – did not leave. “I remember leaving and she just didn’t follow,” Marissa said later in an interview on American National Public Radio. “I saw her on the phone. And the other woman – it was the same thing. She was diagonally across from me and she was talking on the phone and she didn’t want to leave.”

In fact, many people in Marissa Panigrosso’s office ignored the fire alarm, and also what they saw happening 131 feet away in the north tower. Some of them went into a meeting. A friend of Marissa’s, a woman named Tamitha Freeman, turned back after walking down several flights of stairs. “Tamitha says, ‘I have to go back for my baby pictures,’ and then she never made it out.” The two women who stayed behind on the telephones, and the people who went into the meeting, also lost their lives. (read the full article here, alternatively you can download the PDF here)

On Waking from a Dream

On Waking from a Dream

A couple of years ago, just before Christmas, my four-year-old son was admitted to hospital. He’d developed an infection called preseptal cellulitis in the skin around his right eye – his eyelid was angry red and swollen shut. Doctors worried the infection could travel into the optic nerve and then into his brain. He was given intravenous penicillin and monitored around the clock. For seven days, my wife and I stayed with him, and fell into step with life on the children’s ward – our son’s regular doses of medicine, the nurses’ twelve-hour shifts, the doctor’s morning rounds. The snow-muffled streets increased our sense of isolation.

On his first night back home, my son refused to take his antibiotics. My wife and I were alternately pleading, tearful and angry, all to no avail. Finally, I told him a story about the time I had to have my tonsils out, and had run away from two nurses when they came to take me to the operating theatre. ‘I just didn’t want to go,’ I said. My son considered this and, after a few minutes, agreed to take his medicine. At bedtime, with the stories read and the lights shut off, he asked me to tell him again about the time I ran away from the nurses.

That night I was startled awake by a dream, which began to dissolve as soon as I woke. I had an image of myself reaching out to catch a small grass-green lizard that had shot down a dark space between two rocks, vanishing into the earth. The dream felt like a memory – it had the colours of an old photograph, perhaps something that had actually happened to me when I was a boy. I thought the dream might have something to do with my son’s illness, but what? Then I remembered another detail from the dream, the four letters S, I, D, A.

I lay in the dark for a few moments running after the dream but failing to remember any more. Frustrated, I got out of bed, went to the kitchen and ran myself a glass of water from the tap. The green digital clock on the oven said 01.25. I took my glass and went to the living room at the top of the house. I sat there in the quiet, the hush interrupted only occasionally by an all-night bus changing gears on the hill around the corner. (read the full essay at Granta)